- Home

- Tom Savage

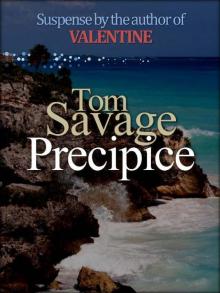

Precipice

Precipice Read online

“It’s a pleasure to welcome Tom Savage. Precipice is an impressive debut.”

—Lawrence Block

“A subtle, well-crafted tale of deceit and madness among the rich.”

—Chicago Tribune

“A stylish and accomplished novel . . . terrific . . . wonderfully complex . . . if Hitchcock and Noel Coward had gotten together—and if they’d had a talent for crime fiction—they might have come up with something like this.”

—Jonathan Kellerman

“A pulse-pounding thriller with a twisting plot and a surprise ending . . . a delightfully icy ride through the tropics.”

—Mostly Murder

“The most intricately plotted thriller in years! Just when you think you’ve mastered the puzzle, you find that you have been fooled—again.”

—Ann Rule

“Murder among the beautiful people . . a fast-paced and very suspenseful page-turner.”

—Library Journal

“All the right ingredients—dark secrets in a bright landscape, madness and mayhem among the megabucks—dished out at a dazzling pace.”

—Reginald Hill

“Likable characters romp through a seemingly simple but eventually complex plot, one that Savage has mined with unexpected twists. Readers’ expectations may be blown to bits by the clifftop denouement.”

—Publishers Weekly

“A stunning first novel that presages a brilliant career.”

—Robert B. Parker

“Extremely clever and gripping, marvelously plotted, and thoroughly spellbinding. Tom Savage is a very gifted writer who creates living, breathing characters, wonderful dialogue, and mesmerizing tension. The ending is as good and surprising as anything I’ve read in years. Do not peek at the last page.”

—Nelson DeMille

“Tom Savage brings to the genre a flair for language, reminiscent of the elegant style of John O’Hara. . . . Savage’s characters are well-crafted, believable and three-dimensional . . . a rapid read and difficult to put down.”

—Denver Post

“Just what it says it is: a story on the edge. A twisty plummet, a delightful debut.”

—Donald E. Westlake

“Cool, smart and stylish . . . surprise piles upon surprise, logically and convincingly . . . a natural for the movies.”

—Kirkus Reviews

PRECIPICE

A NOVEL BY

TOM SAVAGE

Copyright © 1994 by Tom Savage

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means. For information, address Writers House LLC at 21 West 26th Street, New York, NY 10010.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

eISBN 9780786753727

Distributed by Argo Navis Author Services

For my mothers—both of them

Marion Eleanor Savage Phillips

Mother

(1917-1958)

Lesley Savage

Mom

. . . Behold me, what I suffer

Because I have upheld that which is high.

SOPHOCLES

Antigone

translated by Edith Hamilton

Contents

Before

Part One: Goddess of The Moon

One Tuesday, August 6

Two Wednesday, August 7

Three Wednesday, August 7 (Continued)

Four Friday, August 9

Five Thursday, August 15

Six Friday, August 16

Seven Sunday, August 18

Part Two: Goddess of The Hunt

Eight Monday, August 19

Nine Wednesday, August 21

Ten Thursday, August 22

Eleven Friday, August 23

Twelve Monday, August 26

Thirteen Monday, August 26 (Continued)

Fourteen Monday, August 26 (Continued)

Fifteen Thursday, August 29

Sixteen Saturday, August 31

Part Three: Goddess of The Dark

Seventeen Sunday, September 1

Eighteen Monday, September 2 Labor Day

After

BEFORE

THE FIRST THING he noticed was that the front door of the house was standing wide open. Then he heard the humming.

Afterward, whenever people asked him about it, he always remembered that it was unusually warm; the kind of day, he would tell them, that made him wish his uniform were not quite so heavy. The sun bore down on his back and seemed to permeate his clothes. On a day like this, even without the jacket, he would break into a sweat within the first five minutes of his shift, and by the time he got home in the afternoon he would be drenched. His wife always forced him to remove his shirt and trousers right there in the living room, and she’d take them immediately to the washing machine in the basement. The good thing about this was that it enabled him to steal a cold beer from the refrigerator and plunk himself down on the couch in his underwear. Sometimes he made it through such a day just dreaming about sitting there in his shorts with the little electric fan aimed at his naked belly, drinking from that frosty bottle. . .

At this point in the narrative he would pause for a moment, and his audience would invariably smile and nod in sympathetic appreciation. Then the smiles would fade as they became aware of the change in his mood, the expression that came into his eyes and the subtle, almost imperceptible deepening of his voice. By the time he continued they would be watching him in silent anticipation, knowing yet dreading what was to come.

On this particular warm Tuesday morning he had paused on the sidewalk in front of the pretty white house on Pine Street, sighing. His home and his bottle of beer were still some six hours away. He slung his heavy canvas bag from his shoulder and rummaged through it. He knew he had something for number 46 today. Looked like a couple of bills. He found the mail, wiped his brow, and trudged up the pathway to the porch.

This week wouldn’t be so bad, he thought. Four days instead of five, yesterday being the holiday. Next month, at his wife’s insistence, he was going to ask for a neighborhood farther from the post office. Then they’d give him a truck to drive around in. He was getting much too old for the foot brigade. . . .

So fixed was the routine of his so-called appointed rounds that he’d already dropped the mail into the box before he happened to notice the door. Coming from the dazzling sunlight into the shade of the porch had dimmed his eyesight temporarily.

Oh, well, he thought. None of my business. . . .

He’d almost turned around to retrace his steps down the walk when he stopped short, arrested by a faint sound from inside the house. He stood on the threshold, scanning the shadows beyond the open door, looking for the source of the soft, high-pitched humming he’d heard a moment before. He recognized the tune, some kids’ thing—“Frère Jacques,” that was it. . . .

“Hello,” he called from the doorway.

The humming continued.

Then his eyes adjusted, and he made out the dark interior of the room.

The moment he saw her, he knew something was wrong.

She was about six or seven years old, he decided. He had no children of his own, and he’d never been particularly good at guessing their ages. She was sitting on the floor in the center of the living room, dressed in a white nightgown. She was staring vacantly ahead of her, and she clutched something to her as she rocked slowly to and fro, humming.

He knew

the young woman who lived in this house by sight. Sometimes she greeted him at the door with a warm “Good morning,” and he would hand her the mail. But she didn’t seem to be around this morning. So why was the door open? And why was the child sitting there in her nightgown at eleven o’clock? Hadn’t school started today . . .?

“Mrs. Petersen,” he called, aware of the hoarseness in his own voice.

The girl did not look up, did not seem to hear him. He searched his mind for her name—he was sure he must know it—but a peculiar dullness was already beginning to set in. He couldn’t think clearly. . . .

“Little girl,” he finally managed to croak.

No reaction. She sat there, rocking and humming.

There were strict rules in his profession. He would never have dreamed of crossing the threshold, of entering someone’s premises, until he saw what it was the little girl was holding in her hands.

Then he saw the blood.

Before he was aware of having moved, he was across the room and kneeling in front of her. He reached out with his shaking hand and touched her face. Only then did she stop humming and look up at him.

“Have you hurt yourself?” he whispered.

He reached over to take the enormous knife out of her hands. She pulled away from him. There was a nasty bruise on her left temple, but otherwise she did not seem to be hurt. He looked down at the blood on her hands and on her nightgown, realizing with a sudden, cold certainty that it was not hers.

“Where’s your mommy?’’ he asked as gently as possible.

She watched him for a moment. Then, as if he no longer interested her, she clutched the knife to her little chest and began to rock again, humming under her breath.

He rose to his feet, gazing around him. There was broken glass everywhere on the carpet. A huge breakfront stood against one wall, doors open, glass shattered, interior gaping. The coffee table in front of the couch was lying on its side, and the bowl of flowers and two ashtrays that had obviously once rested on it had rolled away to lie in various other parts of the room. All the window shades were down. The air conditioner in the far window hummed softly, but the open door had defeated its purpose. The air inside the house was warm and thick, almost stifling.

He raised a hand to his tightening chest as he looked over at the empty dining area and, beyond it, the open door to the empty kitchen. Then he turned to face the archway that led to the other rooms. If he stood still, he knew, he would begin to hyperventilate. He was fifty-seven years old, and twice already he’d come dangerously close to a heart attack. He must move, must act.

Leaving the girl in the devastated main room, he walked slowly, cautiously into the dark hall beyond the archway.

“Hello,” he called again, but by now he knew that no one would answer. The silence in the house was almost palpable.

He glanced around at the four doors, three of them closed. The open door was on the left, at the end of the hall, and the only illumination was the sunlight that poured through it from the bedroom beyond. Looking down, he saw the tiny, bloody footprints on the white hall carpeting, leading from that room to the living room behind him. Even now he was aware of the vague, unpleasant smell.

He willed himself to move. It seemed to take him forever to walk the few feet to the bedroom doorway. He closed his eyes, took a deep breath, and stepped inside.

She was lying facedown in a patch of sunlight next to the bed. Her nightgown—white, like her daughter’s—and the carpet around her were soaked with blood. There were dark brown stains everywhere: on the bed, the walls, the mirror above the vanity table. Blood covered her outstretched hands and matted her pale blond hair.

The stench was overwhelming. He had clamped his hand over his mouth and pinched his nostrils, preparing to kneel down next to her, when he realized the futility of his action. Mrs. Petersen had been lying here for several hours. . . .

The sudden footfall behind him made him gasp and whirl around. The child stood in the doorway, the knife grasped in her left hand. As he watched, she slowly raised the knife in front of her. Involuntarily, he brought his arms up to protect himself. Oh, dear God, he thought. A little girl. . . .

The two of them stood there facing each other, silent, frozen, a grotesque tableau in the little bedroom of the pretty house on Pine Street. Sunlight poured in through the windows, hot against his neck, gleaming on the blond hair and the slick puddles at his feet. Something in the child’s expression, or, rather, her lack of expression—he always had trouble describing it, although he never forgot it—caused him to slowly lower his arms to his sides. It’s the surprise, he remembered telling himself. I’m still taking it all in, assessing the damage, the calamity of it, and I’m not reacting properly. Besides, the very idea is ridiculous. She can’t be more than seven. . . .

Then, at last, the oppressive silence was disrupted. The little girl blinked once, licked her parched lips, and spoke in a soft, dull whisper, staring not at him but at the empty space somewhere beyond his shoulder.

“Mommy’s dead,” she said. “I killed her.”

The knife fell from her hand as her eyes glazed over and her tiny body slumped to the floor.

The first wave of shock washed over him, and later he would not recall his next actions clearly. He must have moved. The child was now in his arms, and he was running down the hall into the living room. Phone, phone, he must find a phone. . . .

The telephone was on the living-room floor, partially concealed by a stray throw pillow from the couch. He held the girl with one arm and reached down with the other. The receiver was dead. The coiled cord leading to the main body of the phone had been severed.

He dropped the useless instrument, cradled the child against him, and lurched through the open front door. Out, out into the clear air, the bright sunlight, away from the smell and the blood and the knife. The girl must have awakened, he supposed. The sound of terrified screaming filled his ears as he staggered down the pathway to the sidewalk.

Only later, when the neighbors began to appear, running toward him from their houses; when they finally took the unconscious child from him; when the wail of a hundred approaching sirens slowly entered his consciousness, did he become aware that the screaming he heard was his own.

He always ended there, with that little flourish, slowly grinning at the astonished expressions that invariably came to the faces of his listeners, unaware that his blithe smile was born not of humor but of his own acute embarrassment. He told the story many times, whenever people asked, less and less frequently as time passed and everyone began to forget about it, until eight years later, when his wife died and he retired from federal employment. After that, for reasons of his own, he stopped repeating it altogether.

PART ONE

GODDESS OF THE MOON

ONE

TUESDAY, AUGUST 6

THE IDEA OF MURDER, once formed in her mind, simply would not go away. She’d been working on the plan for quite some time, waiting—patiently, she thought—for just the right opportunity to set it in motion. She’d tackled the situation as she would a crossword puzzle, or one of her beloved anagrams or word-association games. When she’d at last figured out the ideal solution, she’d jumped right in. She’d cleared the field, so to speak, and now she was—slowly, painstakingly—baiting the trap. It was going to work; she had no doubt of that. It was why she was here now, today. And it was apparently going to be easier than she’d expected. . . .

Kay watched the girl from her chaise longue in the shade of a palm, trying to decide on the best way to approach her subject. She was grateful for the cool, concealing shadow. The intensity of the midafternoon sun on a cloudless day was something that even seven years of living in St. Thomas had failed to make less painful. That’s what you get, she mused, for allowing your husband to talk you, an Irish redhead, into moving to the tropics. Not so bad, really, as long as you could lie in the shade with a tall glass of rum punch within easy reach. She took a sip: Dutch courage. She’d alwa

ys been shy around people she didn’t know. She hated breaking the ice, which is what she would have to do. She would have to get off of this chair and walk over to the girl, engage her in conversation. Present her case, as her late first husband would have said. Her new husband, Adam, was not a lawyer.

The girl stood before her easel near the shoreline, digging her bare toes into the warm white sand and contemplating her half-finished watercolor. If she was aware that she was being watched, she gave no sign of it. To all appearances, she had nothing on her mind but the elusive hues of the rich blue, wind-whipped Caribbean she was trying to capture with the artificial, oddly inadequate spectrum in the gleaming silver tubes of her paintbox. No shady palms for her: she welcomed the sunlight bearing down on her naked limbs, the breeze in her hair. She seemed perfectly at ease, a perfectly capable young woman. Her only problem, it would seem (if you were to ask the woman watching her), was keeping the watercolor pad from taking flight down the beach, leaving her and the bare easel to cope as best they could. She held a medium-sized brush in her left hand, and with the right one she absently adjusted the bra of her bikini. Then the hand traveled up to capture a stray lock of her dark, shoulder-length mane and push it behind her.

She’s really quite a lovely young woman, Kay decided. Tall—just about the same height as Kay herself, who was five-eight—and possessed of that willowy grace one usually associated with dancers. Looking down at her own body, Kay shook her head and let out a long sigh. It was hard to feel willowy after one had borne a child. Lisa was twelve years old now, nearly thirteen, and Kay had never been willowy in the first place. Oh, well, heigh-ho. . . .

The girl, seemingly oblivious of Kay’s scrutiny, dropped the medium brush into the jar of cloudy, blue-violet water on the tray table that the hotel management had so kindly provided. She picked up a long, thin detail brush and placed the wooden end between her teeth. She chewed absently, gazing out over the water.

The Devil and the Deep Blue Spy

The Devil and the Deep Blue Spy Scavenger

Scavenger A Penny for the Hangman

A Penny for the Hangman The Woman Who Knew Too Much

The Woman Who Knew Too Much Mrs. John Doe

Mrs. John Doe The Spy Who Never Was

The Spy Who Never Was Precipice

Precipice